Hello fellow rice fans and Happy New Year! This month I thought about how many menu settings there are on my rice cooker and how I never use anything but “white rice”. What if I made all the rice types available, just to see how they work? Do you think it would really make a difference? I put my rice cooker to the test!

Jasmine

We don’t eat much Jasmine rice at our house—we almost always make Japanese short grain so I’ve never experimented beyond “Regular” or “Quick”. I can tell you for a fact that “Quick” only takes about 35 minutes but there is a difference. You sacrifice a subtle, overall fluffiness that you get from soaking the grain in water for that extra time and it does affect the texture. I’m embarrassed to admit I use that setting a lot, especially if I’m having curry rice. If I’m topping my rice with curry, I’m just not all that fussy about my rice, you know what I mean?

But we had Thai food for dinner, and I wanted authentic Jasmine rice to go with it. So we decided to cook our own instead of eating the takeout one from the restaurant.  Zojirushi warns in their manual that it may cook firmer than normal depending on the brand of the rice, but ours turned out perfectly. It was loose and not sticky, like Jasmine is supposed to be, and the fragrance of the rice really comes through when it’s fresh.

Zojirushi warns in their manual that it may cook firmer than normal depending on the brand of the rice, but ours turned out perfectly. It was loose and not sticky, like Jasmine is supposed to be, and the fragrance of the rice really comes through when it’s fresh.

Porridge

This setting is used to make the watery rice gruel called “okayu” (pronounced oh-kah-yoo) that we eat when we’re not feeling well and have no appetite. It’s warm, comforting and easily digestible. The cooker did its job and left the rice in this soupy texture. Normally regular short grain is used for okayu.

Personally, I like to have mine with the rice sprinkles that you can get at the Asian markets. It adds a great flavor to the rice, and if you have it with a pickled plum it’s healthy for you too. If you have this setting on your rice cooker, try this; I promise you’ll find it amazing. You don’t even have to be sick.

Oatmeal

Even though our cooker doesn’t have an Oatmeal setting, you can use the Porridge menu to make oatmeal. We made a slight adjustment by adding twice the amount of oatmeal so that it wouldn’t come out too watery like the rice gruel. For more detailed information go to this page in Zojirushi and it will tell you exactly how to cook oatmeal and other types of rice.

The advantage to using the rice cooker vs. in a pot on a stove? You don’t have to keep stirring it and watching it. We made it for breakfast and had a self-serve Oatmeal Bar.

Sweet

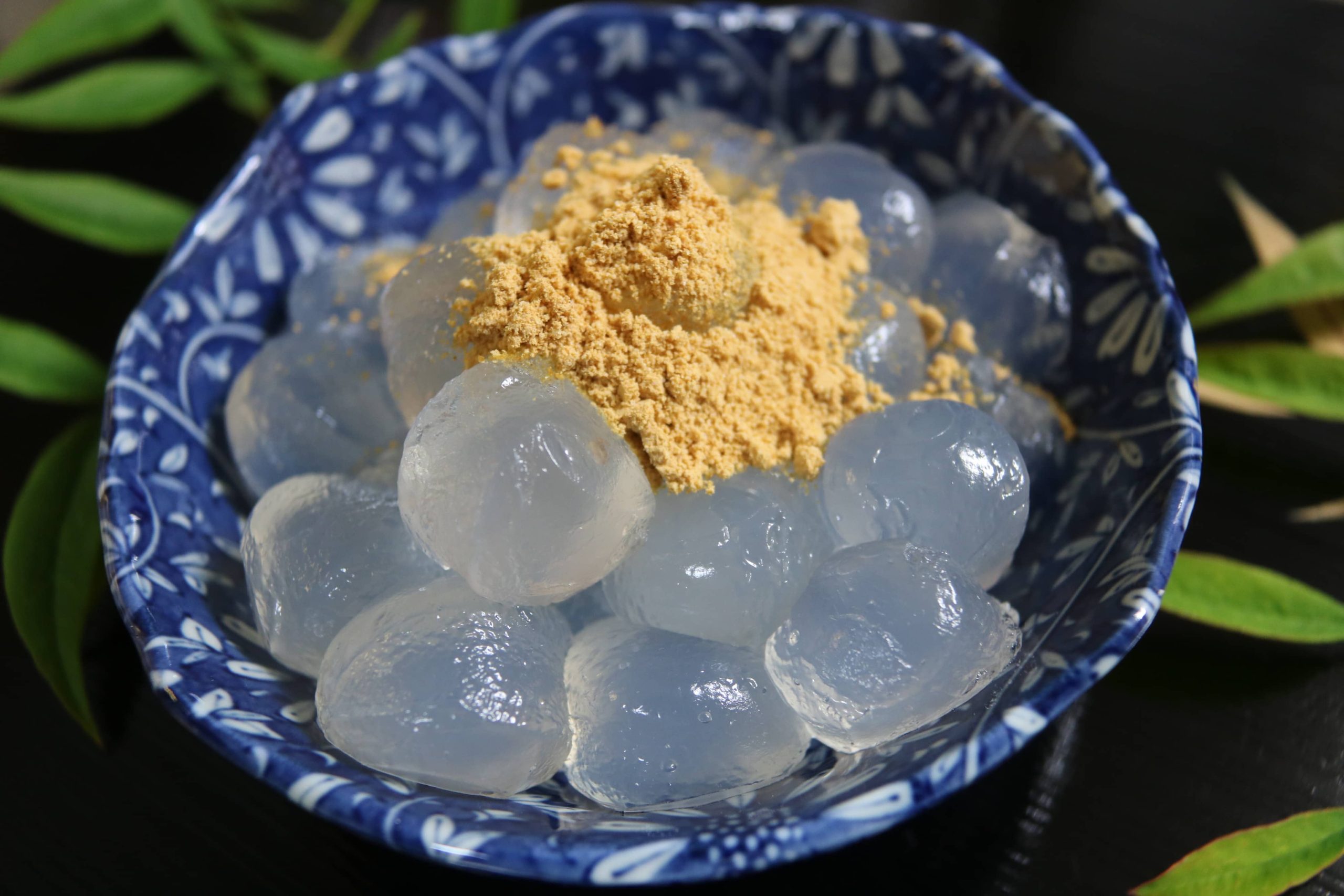

The Sweet setting is used for mochi-gome (mochi rice). You can make a lot of Japanese style traditional desserts using this extra-glutinous rice, but all you need is a stand mixer to make real mochi. After it cooks, transfer the hot mochi rice to your mixing bowl. The Sweet setting does everything, so as long as you’ve measured correctly, you’ll get the super sticky texture you want. We didn’t have a dough hook for the mixer (recommended), so we used the flat beater attachment and it still worked fine. Just knead the mochi rice until you get real mochi.

Make sure you use a lot of corn starch to make the mochi easier to handle. WARNING: Sticky! If you can get red bean paste at your store, you can fill your mochi patties and form them into homemade Daifuku, a traditional dessert.  My impressions of homemade mochi: if you have a chance to do this, do it! The freshness and natural sweetness of the rice gets enhanced, and the flavor is unbeatable. Store bought mochi doesn’t even come close. But the caveat is that clean-up might be a turn off to some—it really is hard to get off of everything. If anyone has any ideas about this let me know.

My impressions of homemade mochi: if you have a chance to do this, do it! The freshness and natural sweetness of the rice gets enhanced, and the flavor is unbeatable. Store bought mochi doesn’t even come close. But the caveat is that clean-up might be a turn off to some—it really is hard to get off of everything. If anyone has any ideas about this let me know.

Mixed

The Mixed setting is used to make Takikomi Gohan, type of Japanese rice dish that you can make right in the pot from a kit that you can buy at the market. All the ingredients are in the box, so all you have to do is set it and forget it.

The extra cooking time allows the dashi flavored soup stock to infuse better into the rice so you get an umami flavored rice dish that goes perfectly with broiled fish or any light entree.

Here are two kinds of Takikomi Gohan that we made with the “Mixed” setting. Both were complete kits. This one is a mixed mushroom dish with bits of salmon.

If you buy one that is more expensive, you can get one with chestnuts. Just FYI, both of these Takikomi Gohan dishes are kits that come with everything you see, right out of the box. So easy!

Just FYI, both of these Takikomi Gohan dishes are kits that come with everything you see, right out of the box. So easy!

Stay tuned for another post where I try the other menu settings on my rice cooker. Hopefully I’ve inspired you to explore your own rice settings—there’s so much you can do with it!

Products used in this post: Rice Cooker NP-HCC10

Please note that these recipes were not tested by Zojirushi America.

All images by Bert Tanimoto ©2024

Our Food Lover’s Tour continues this month in Gifu Prefecture, home of the famous gohei mochi!

Our Food Lover’s Tour continues this month in Gifu Prefecture, home of the famous gohei mochi!