Varietals. Aromas. Complexity. Palettes. Terroir.

Varietals. Aromas. Complexity. Palettes. Terroir.

Wine inspires passion, joy, camaraderie, sweat, tears and toil. Cultures and industries throughout history have focused on the creation of wine from crushed and fermented grapes. And this infinitely varied drink is becoming a staple in modern Japanese cuisine.

Wine is made from the grapes, typically of the Vitis vinifera family of grapes, which originate from the area that spans Western Europe through the Middle East until the banks of the Caspian Sea. From ancient times, grapevines were highly prized and traded, and grape cultivation is now common on every continent on Earth except for Antarctica.

Grapes were introduced to Japan during the Nara Period (710 – 794 CE), at a time of diplomatic, cultural and religious exchanges between China and Japan. Grapevines were cultivated in Yamanashi, Yamagata and Nagano Prefectures along with some areas in Hokkaido. Until the 16th century, when Jesuit missionaries from Portugal brought wine as gifts for the Japanese nobility, grapes were simply consumed as fruit, not wine. Japanese people tasted wine only through the missions, and the unfamiliar beverage did not gain popularity until the 19th century, during the Meiji Era (1868 – 1912). Cross-cultural exchange thrived during the Meiji Era, and the diplomats of the Iwakura Mission famously traveled to America and Europe, gathering information about many advances and industries, including viticulture. The first native Japanese wine was attempted using sake equipment and koshu grapes that were cultivated in Yamanashi Prefecture.

Today, wine drinking is increasing in popularity and many varietals pair beautifully with Japanese food. According to Peter Kasperski in Food & Wine, “Sake is legendary in Japan because of its ability to offering subtlety and nuance – just like dishes such as sashimi. Wines with similar subtlety and nuance tend to fall into the category of light, white and crisply acidic, with bright fruit notes… with a chameleonlike way of matching a variety of dishes.”

These characteristics are inherent in two of the most popular indigenous Japanese grapes: the white “koshu” and the red “Muscat Bailey A”. These two grapes make up the majority of grapes used in native Japanese winemaking. Wine from koshu grapes is typically refreshing, with notes of grapefruit and lemon and with light acidity. Wine from Muscat grapes is also light in acidity, with subtle notes of cherries, peaches, rose petals, apricot and orange blossoms. Japanese winemakers utilize the well-known winemaking process developed by the French, where carefully cultivated grapes are harvested, crushed and pressed, then mixed with yeast, sugars and water into a mixture called a must. This mixture is fermented, then strained, or clarified. The clarified liquid undergoes a second fermentation, after which it is bottled and aged. Once produced, Japanese wines are categorized as kokunaisan, wine made exclusively from domestic materials; kokusan, wine made from imported ingredients but fermented in Japan; and yunyu, imported wine that is bottled in Japan.

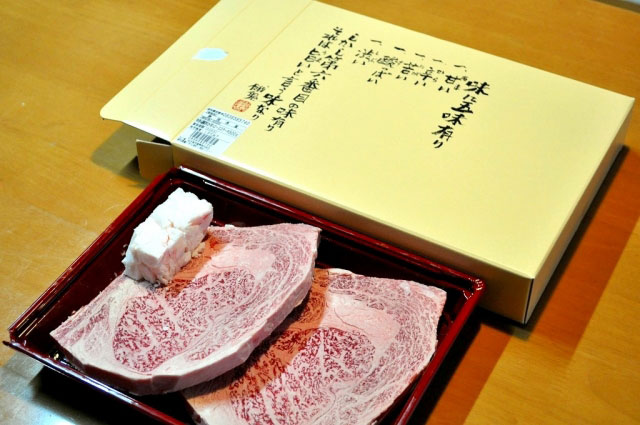

Japanese food pairs beautifully with wine. Sashimi and sushi lend themselves to crisp white wines, including light, sweet Rieslings, mineral-rich, full-bodied Pinot Blancs and dry koshu-based wines. Fried foods such as tempura and karaage ideally pair with sparkling wines as well as light, mineral-rich red wines, such as Sancerres, Muscats and even some varieties of rosés. And grilled meats such as yakitori and teppanyaki complement fuller, fruit-forward white and red wines such as Pinot Noirs, Cabernet Sauvignons, Sauvignon Blancs and certain Bordeaux.

Almost any type of Japanese food is delicious when paired with wine!

We hope you try your favorite wine with some of our favorite foods, and as always, don’t forget to share your best pairings with us!